Hänsel und Gretel

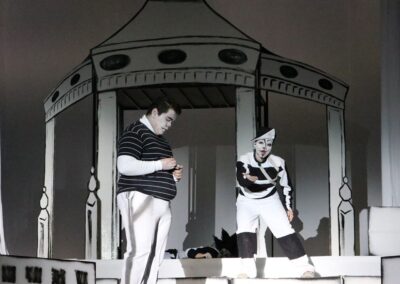

The year after Così fan tutte, I returned to the San Luís Potosí Festival to direct Hänsel und Gretel, in similar conditions but with the added complexity of an outdoor performance. After several location changes, the final venue became a colonial square—visually rich, but difficult for focusing audience attention. From the first proposed site, I preserved the idea of the town’s music kiosk; from the second, a forested park, I drew the contrasting idea of a deliberately artificial world, for which I developed a black-and-white, two-dimensional scenography with touches of red—surreal, graphic, and visually assertive enough to stand out in the urban environment while remaining inexpensive and flexible.

This aesthetic was also dramaturgically grounded: the kiosk in San Luís Potosí is inhabited nightly by families living in precarious conditions; this reality strongly echoed the opera’s opening themes of hunger, parental dysfunction, and childhood vulnerability. I translated then these social parallels into a dream-logic vocabulary: schematic cardboard “Lego” structures, a drawn, two-dimensional kiosk, and video projection that transformed the square into a collective subconscious. This approach gained further resonance because Hänsel und Gretelwas written the same year Freud defined the subconscious; it also linked to the Huichol worldview, in which dreams guide one’s life mission.

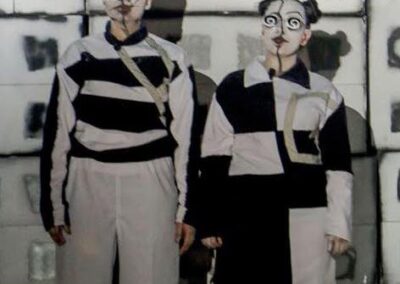

Costumes followed the same surreal graphic vocabulary. The witch—consciously designed as a fusion of mother and father—embodied the fear, desire, and emotional confusion at the centre of the children’s experience. In the opening, a tableau of small-town life introduced the kiosk as civic symbol. The first part unfolded in a world of cardboard and passers-by, disrupted by parental violence and addiction; the “forest” became the concrete jungle to which many Mexican children migrate. Boxes were stacked into fragile skyscrapers; survival turned into small thefts; night arrived as a giant serpent-Sandman whose bite sent the children into a dream.

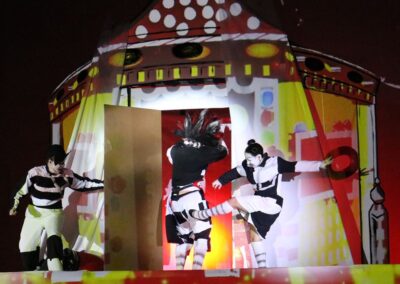

The dream sequence, through video-mapping, transformed the kiosk into the witch’s house: a burst of colour, movement, and uncertainty. After the oven explosion, reality snapped back to black-and-white. The witch’s body reappeared as a cake torn apart by parents and onlookers in a frenzy—a deliberately uncomfortable image of social cannibalism. Yet from the debris, the children discovered a single coloured object—a reflective “mirror egg”—a fragile symbol of their new consciousness and purpose.

As in Così, I integrated projected questions into the dramaturgy—this time centered on the responsibilities of parenthood and the function of dreams: What do we want for our children? What price do we pay to feel loved? What did you dream of as a child? Who is the witch?These texts, combined with short quotations, opened the opera’s psychological and social themes to audiences of all ages.